How would I summarize Hocaefendi’s life in one sentence? A single sentence that could encapsulate his entire life. In the first few days of my endeavor seeking an answer to this question, I found myself weary under the weight and intensity of the thoughts crowding my mind as I tried to form such a sentence. I have spent nearly thirty years immersed in his ideas and thoughts, organizing and analyzing them from religious, social, historical, and contextual perspectives. In recent years, my focus has been on exploring the authentic, legitimate foundations, both material and spiritual, that shaped his ideas and the movement of volunteers he inspired. Throughout my studies, I have constantly searched for a way to distill it all into a single sentence.

The soundness and legitimacy of a cause can be tested on multiple grounds, drawing testimony from religion, humanity, conscience, history and societal common sense. Hizmet is a movement of volunteers which derives legitimacy from all these areas and has won the conscientious approval of millions worldwide. Only a handful religious and social movements in history have received an acceptance and recognition as broad as the one Hizmet has.

As everyone knows, Hocaefendi’s will was opened recently and shared on social media. Personally, I view this historical document as both a testament to his modest life and as a validation of his religious, humanistic, moral, and conscientious legitimacy. As a founding leader, he demonstrated to millions the depth of his ethical consistency in managing the movement’s resources.

Having spent some years in his teaching circle, I’ve been somewhat aware of this will for the past thirty years. He would occasionally reference it in different contexts. Decades ago, we were already aware of his deep regret for small debts incurred fifty years earlier and his relentless efforts to track down and repay those creditors.

We witnessed him rigorously accounting for every aspect of his life. Everyone close to him could attest to his unwavering scrupulousness in religious, moral, and conscientious matters. Yet, even with this awareness, I must admit that reading his will left me unsteady, prompting an unprecedented level of self-reflection. At that moment, it felt as if time stood still. I am at a loss of words to describe the sense of humility and shame I felt in the face of a life spanning more than eighty years lived in simplicity while leading a massive movement whose influence, message, and synergy have reached millions across the globe.

And yet, for years, people have said so many things about him. Some even fabricated outrageous claims: that he controlled billions of dollars, owned vast olive groves stretching from Edremit to Ayvalık (in Turkey), and lived a life of luxury in gilded mansions on private estates—slander so shameful that I blush merely repeating it. Even those who spread this slander knew he had spent his life on a simple mat. In any case, I do not wish to taint your mind with such falsehoods. For me and for millions, his will has now become a historic document that summarizes the life of this towering figure. It stands as the greatest witness to both his spiritual character and to the movement of volunteers he founded—affirming the religious, human, moral, social, and historical legitimacy, as well as the ethical consistency, of the movement. I see it as a historic testament to the integrity of the volunteers who embody this service.

What remains from a spiritual and moral hero is this humble, simple, yet profoundly historic document. He was a religious leader and a guide who carefully kept his closest ones away from the material resources of the movement and settled in the hearts of millions. Yes, of course, there are the schools, myriads of volunteers, lives devoted to humanity, monumental services, and historic bridges of dialogue built among diverse cultures, all bearing witness to this legacy. Yet, the message conveyed by this modest document feels like a universal call to humanity’s conscience and common sense, inviting us to a life of selflessness and prophetic integrity in an increasingly materialistic, worldly, and self-centered world.

When I read his will, the first thought that came to mind was the incident following the Prophet’s passing. His wives sent Uthman ibn Affan to Caliph Abu Bakr to request their share of inheritance from Khaybar and Fadaq. When Aisha heard about this request, she quoted the following words from the Prophet: “We Prophets do not leave wealth as inheritance; what we leave behind is charity.” Upon hearing this, they withdrew their demand. Although there are different narrations, in one version, it is stated that scholars are the inheritors of the Prophets. This inheritance, when taken in its absolute meaning, suggests that true inheritors are not only those who inherit knowledge and wisdom but also those who inherit the pain, suffering, trials, poverty, and deprivation endured by the Prophets. This document stands as a testament to a life marked by hardship and sacrifice.

They once asked Rumi about the “state” of a lover (of God), and he responded, “It is like the sleep of one who rests on a pillow of thorns.” When I first read this in high school, I thought it was merely a poetic metaphor. I was somewhat familiar with the kind of life dervishes like Rumi and Yunus Emre led from Sufi literature. However, until I met Hocaefendi, I always looked to the past, to the ascetic lives of the dervishes of the eighth and ninth centuries, as the embodiment of this statement. I had assumed that such a life could no longer be practiced in modern times. Hocaefendi, I came to realize, was the sole exception.

Without a doubt, any attempt on my part to describe Hocaefendi’s state would be a second- or perhaps third-hand account. However, as a note for history, I can attest to this through my own observations, using Rumi’s metaphor: not only was Hocaefendi’s pillow thorny, but his entire bed and cover seemed laden with thorns. He lived his entire life that way. I believe that his fellow volunteers, close companions throughout different phases of his life, as well as his relatives and others who knew him well, would affirm these words.

In sum, this will stands as the greatest testament to his life of suffering, hardship, and profound concerns for humanity. May his soul rest in peace, may his place be the highest level of Paradise, and may his memory be cherished in our minds. I extend condolences to all who love him throughout the world.

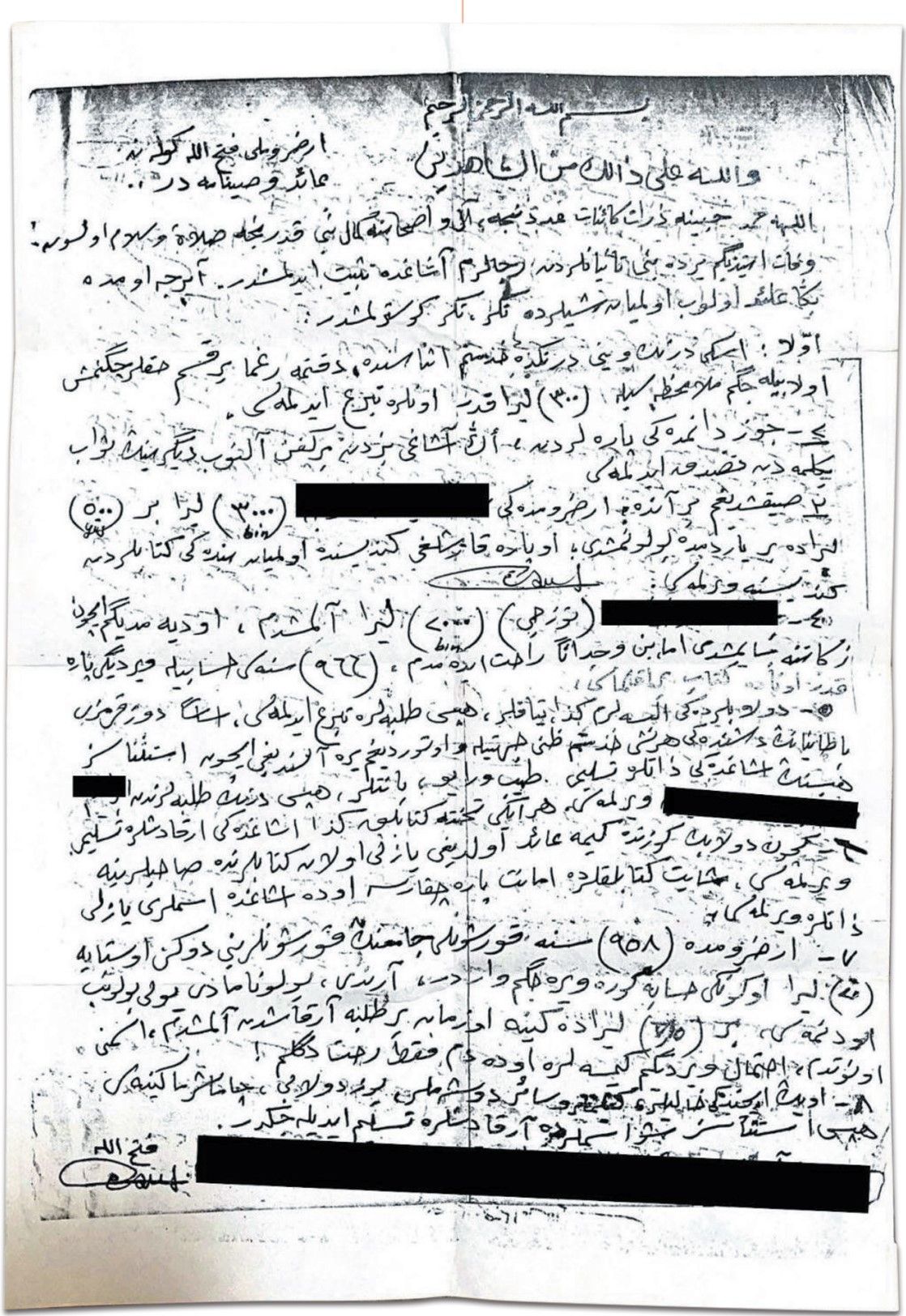

The Will & Testament of M. Fethullah Gülen

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

God is a witness over this.

This is the will of Fethullah Gülen from Erzurum.

Praise be to God, peace and blessings be upon the Beloved of God to the number of atoms of the universe, and upon his Companions to the degree of perfection of that noble Messenger.

From those who know me and happen to be at the place I die, I request the following. As to which items in my home belong to me and which do not have also been identified.

Firstly: Assuming the possibility of inadvertent misuse during my service, donate 300 TL (Turkish Lira) to both the old and the new foundations.

- From the money in my wallet, a shroud of the cheapest cloth is to be purchased, and the remaining amount should be given to charity, without any expectation of reward.

- When once I was in financial hardship, (such and such person) in Erzurum had given me 3,000 TL (approximately $87) on one occasion and 500 TL (approximately $14.50) on another. Any of my books not already in his library should be given to him to compensate for that amount.

- I borrowed 2,000 TL (approx. $57) from (such and such) in 1966. Although he considered it alms and did not seek repayment, I do not have a clear conscience about it. Therefore, books equivalent to the value of that amount should be given to him.

- My clothes in the wardrobe and the bedding are to be donated to students. Except for the plain red blanket, everything was provided for my use on the assumption of my service. These items, without exception, should be distributed to the individuals I name below. The tape player, radio, and cassettes should also be given to students (…) and (…) at the foundation. Both wooden bookshelves should likewise be delivered to the friends named below.

- As for the books in the drawer of the little cabinet, the names of their owners are written inside. They too are to be delivered to their owners. If any money is found between the pages, it should also be given to the individuals named below.

- In 1958, I borrowed 20 TL from a craftsman who was laying the lead for the dome of the Kurşunlu Mosque in Erzurum. Efforts to find him were unsuccessful, but he should be located, and the debt paid according the value of that day. I also borrowed 75 TL from a student whose name I have forgotten. While I believe I may have repaid this debt, I remain uneasy about it.

Any carpets, rugs, and other spreads, as well as the fridge and washing machine, should all, without exception, be delivered to the following individuals: (…), (…), (…), (…), (…) A copy of this will can be found in the pocket of one of the jackets in my room.

M. Fethullah

Note: The names directly mentioned in the original text are kept private. It has been reported by his family and students that Fethullah Gülen already paid all the debt listed in the will at different times since then.